Artists and creatives have always been instrumental in identifying and driving the zeitgeist. The application of AI is providing new ways for us to be creative.

Creativity and AI

As an artist, writer and manager of projects and people I’ve been invited to share my thoughts on Creativity and AI; specifically on whether AI is likely to help or hinder creativity.

My simple take is this: AI is a spectacular example of humans using their creativity to make tools which make our lives easier. And tools are made to be used. So our ingenuity both brought AI about and is integral to it being used at all… whether or not we consider the outputs of AI as authentically creative is a different question, to which the simplest answer is ‘it can be.’

What makes any creative endeavor authentic? As it’s close to my own heart, let’s think about art. Art objects aren’t limited to those crafted by an artists’ own hands. Aside from found art (exemplified by Duchamp’s urinal set on a pedestal) and conceptual art (presenting an idea as art) even hand made art objects aren’t entirely clear cut. There is a long history of artists having studio assistants or commissioning other artisans to execute some or all of their planned artwork. Arguably all art is conceptual – dependent on an individual having the idea that ‘this is art’.

AI in the creative industries

Artists and creatives have always – not as individuals, but as groups within our societies – been instrumental in identifying and driving the zeitgeist. Artists moving into an area is now recognised as a first step towards gentrification, as others are drawn to the communities they create. Artists were among the first to exploit the potential of NFTs (Non-Fungible Tokens), leading to previously relatively unknown artists such as Beeple making eye-watering sales and establishing names for themselves, alongside established art-world boundary breakers like Banksy and Damian Hirst.

There is similar enthusiasm for the latest innovations in AI. The most powerful new tools are undoubtedly those built on Large Language Models (LLM) whose predictive and pattern-matching abilities can generate new linguistic or visual content in an instant. This year an AI generated image, “Théâtre D’opéra Spatial” won it’s creator Jason Allen first prize for emerging digital artist at Colorado’s State Fair (not without controversy.) Meanwhile, MOMA is hosting an artwork created by Refik Anadol which uses AI to create an immersive experience using machine learning trained on MOMA’s collection and which is responsive to the immediate environment.

This enthusiasm from creatives is matched by a race to release the latest most impressive tech to win over users and dominate this new marketplace. Meta have launched Make-A-Video which generates video content from text inputs; meanwhile Open AI’s DALL-E, generating ever more complex still images from text inputs, is now available to anyone who wishes to sign up. Stable-Diffusion can be tried with or without a log in. And while text-to-speech programmes have been available for long enough for us not to blink an eye at, we can still be impressed at text to music by the likes of Jukebox (by Open AI) or entertained by image to music from Melobytes. We can even, if we choose to, now read novels, screen plays and poetry generated by AI; testament to the increasing sophistication of what LLMs where first conceived to do – to generate language that passes for that produced by a human.

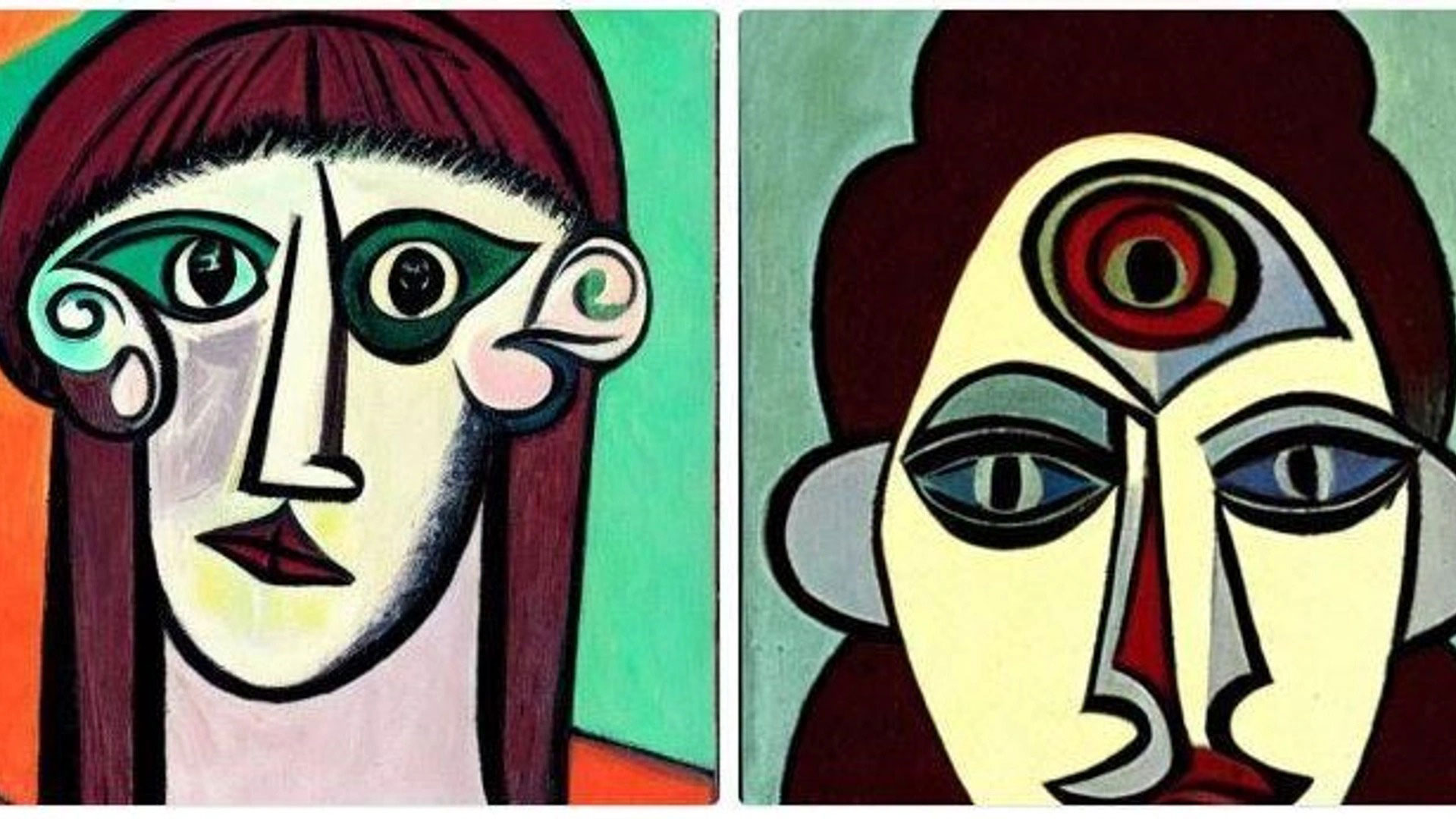

Which of the following images is taken from a real Picasso painting?*

Credit where credit’s due

As AI image generation comes on in leaps and bounds, what is slower to develop is any system for crediting the plethora of artists whose work has been used to train the AI. On balance, Picasso won’t have much to say about his work being used in this way… in any case there have already been decades of Picasso pastiches, and it’s generally agreed that he did alright for himself during his lifetime. It’s a different ball game for living artists who may be struggling to get recognition and remuneration for their original content, and suddenly find they are in competition with tech that mimics their style. Artists themselves are inevitably at the forefront of working to address the issue of ‘real’ human output directly informing new images. Have I Been Trained is one such initiative that enables searches of the 5.8 billion images that have been used to train the most popular AI art models.

While there are very valid concerns that counter the enthusiasm for the progress of AI art, this is the start of something that is not going away. The art world, like the rest of the world, must and will adapt. Hopefully enhancing rights and recognition of artists and creatives along the way…

What next for AI artistry?

Wider possibilities for applying AI to artworks are breathtaking. Consider interactive art that adapts to a space, responds to viewers gestures, vocalisations or mood; or even changes according to the weather, time of day or latest news cycle. There are options for blurring the boundaries of artist and viewer still further by AI customisable art, art that adapts based on viewer preferences, and facilitating collaboration between artists/AI operatives/AI engines.

Stepping back from the brink of what is currently cutting edge AI for a moment, in years passed we might have considered Computer Aided Design or image-editing software, both now industry standard, to raise similar questions about authenticity and authorship, and whether they might harbor the decline of established crafts. While there has unarguably been a huge shift to digital photography, the number and variety of images being produced and shared has skyrocketed; and meanwhile there has remained, among artists, a steadfast interest in techniques that use film and solar plates. Similarly CAD has not and will never replace the making of handcrafted artefacts – which we love to make, and to own – but provides us with different ways to be creative, and on a larger scale.

The art in artificial intelligence

Back to the basics: consider our ideas of artificial, artifice, art (the root of them all), and intelligence:

‘artificial’ is something that is not natural, or something that is made by humans.

‘artifice’ is a clever or ingenious device or expedient; a stratagem.

‘art’ is a skill that is developed through practice and study over time. Or alternatively, of the creative ‘art’, Picasso famously said ‘Art is the lie that makes us realise the truth.’

‘Intelligence’ is the ability to acquire and apply knowledge and skills. This could involve learning from experience and/or abstract thinking.

The application of AI is augmenting our intelligence and providing new ways for us to be creative. The use of the technology, and associated intentionality and authorship of its outputs, however complex these become, rests firmly with us. Incidentally, can you tell which parts of this short article were generated by AutogenAI’s General Language Engine? (As Forbes have so eloquently set out, in fact ‘the biggest opportunity in generative AI is language, not images’.)

The possibilities of AI-enhanced art are endless! As are the number of ways we could, and do, choose to scratch a mark into a piece of stone, or make a pencil drawing on paper.

“The true sign of intelligence is not knowledge but imagination.” – Albert Einstein

*Answer: None of them. These images were all generated in about 10 seconds by giving Stable Diffusion the prompt ‘Picasso-style woman’s face’.